Project 1 – Oxygen Budget

We saw in class that the highest concentrations of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) are in the mid-depth Pacific ocean.

- In Absalon, under files, download

theocean.ncand plot the global distribution of DIC at 2000m depth, in an east-west cut, and a north-south cut across the Pacific. The file contains output of a commonly used climate model (Nielsen et al. 2019, Paleoceanography). It helps to usexarray, and a primer for how to use it to analyze model simulations is provided at: https://veros.readthedocs.io/en/latest/tutorial/analysis.html - Use the Reynolds averaged tracer equation to determine the main sources and sinks of DIC in the mid-depth North Pacific (the values for horizontal and vertical turbulent diffusivity are 800 and 1-e5 m²/s, respectively). Pay attention to the units!

- Describe in your own words and based on your analysis above what explains the DIC maximum in the North Pacific.

- Form groups of 2 or 3 and hand in the answers as PDF by Sunday, midnight (i.e. email to mjochum@nbi.dk).

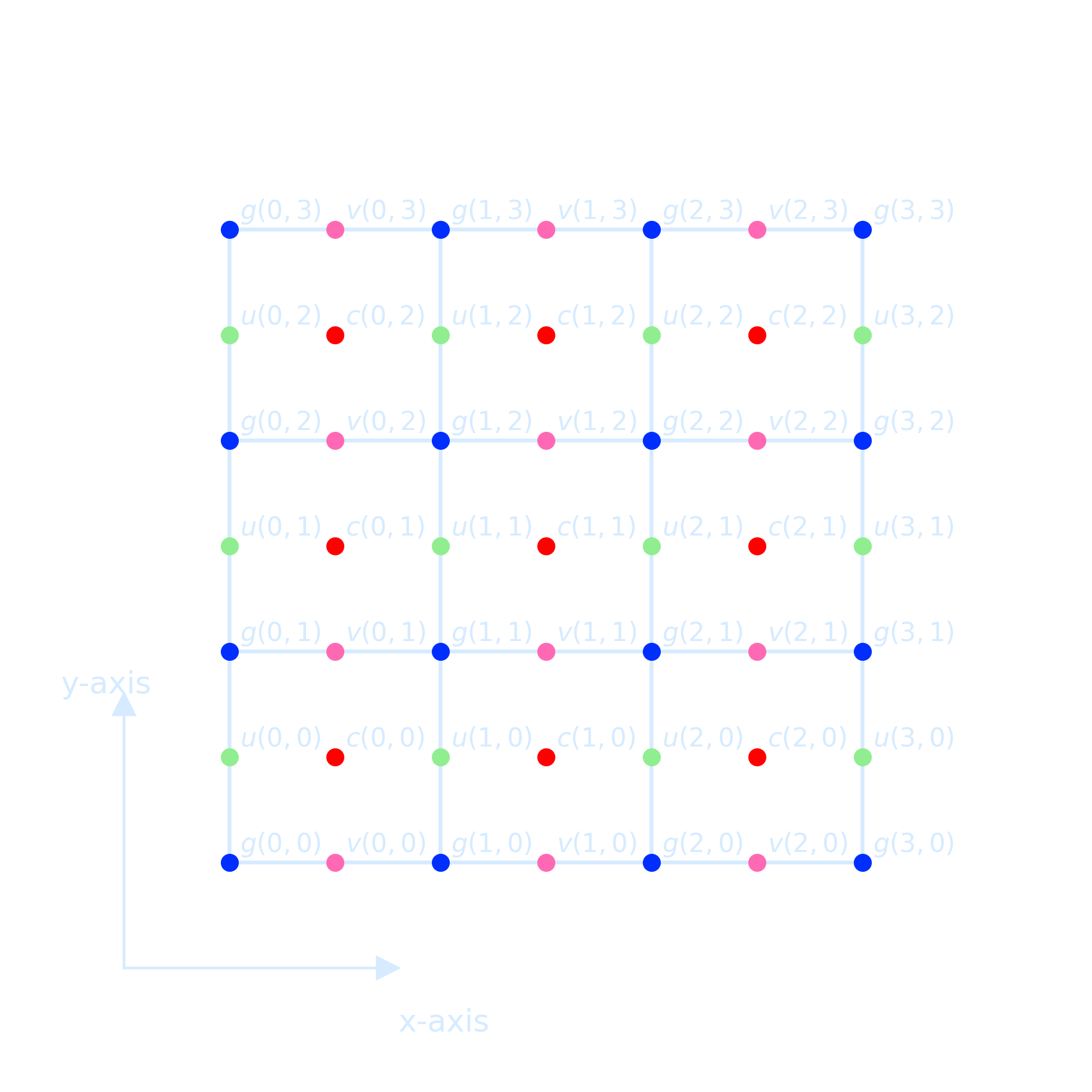

Staggered Grids

We must choose a grid in such a way that both volume \(V_1\) and \(V_2\) can be accommodated and the

natural way to do

that is take \(u\) and \(v\) in different nodal points.

Such an arrangement of nodal point is called a staggered grid

When discretizing a scalar equation, it is often choose the grid that the boundary conditions can be easily implemented.

- Fluid variables live on “Arakawa Grids” (Arakawa and Lamb 1977)

- Variables’ positions are offset

- Finite-volume calculations must account for this to get correct results

class ArakawaCGrid(object):

def __init__(self, nx, ny, Lx, Ly):

super(ArakawaCGrid, self).__init__()

self.nx = nx

self.ny = ny

self.Lx = Lx

self.Ly = Ly

self.true_slice = [slice(1,-1)]*2 # slice of state arrays w/out BCs

# Arakawa-C grid

# +-- v --+

# | | * (nx, ny) phi points at grid centres

# u phi u * (nx+1, ny) u points on vertical edges (u[0] and u[nx] are boundary values)

# | | * (nx, ny+1) v points on horizontal edges

# +-- v --+

self._u = np.zeros((nx+3, ny+2), dtype=np.float)

self._v = np.zeros((nx+2, ny+3), dtype=np.float)

self._phi = np.zeros((nx+2, ny+2), dtype=np.float)

self.dx = dx = float(Lx) / nx

self.dy = dy = float(Ly) / ny

# positions of the nodes

self.ux = (-Lx/2 + np.arange(nx+1)*dx)[:, np.newaxis]

self.vx = (-Lx/2 + dx/2.0 + np.arange(nx)*dx)[:, np.newaxis]

self.vy = (-Ly/2 + np.arange(ny+1)*dy)[np.newaxis, :]

self.uy = (-Ly/2 + dy/2.0 + np.arange(ny)*dy)[np.newaxis, :]

self.phix = self.vx

self.phiy = self.uy

self.shape = self.phi.shape

self._shape = self._phi.shapeCommands and Codes

The pwd command writes to standard output the full path name of your current directory (from the root directory). All directories are separated by a / (slash). Check the current directory:

!pwdList files in the current directory:

!lsFor example, if you want to check inside the erda_mount directory:

!ls erda_mount/To inspect the NetCDF file theocean.nc located in the same folder as your notebook (/home/jovyan/erda_mount), you can do the following directly within a notebook cell:

!ls /home/jovyan/erda_mount/theocean.nc # Verify the file exists firstQuickly inspect the contents using Python and the xarray package, here is a detailed user guide for it

!pip install xarrayimport xarray as xr

# Open and inspect the NetCDF file

ds = xr.open_dataset('/home/jovyan/erda_mount/theocean.nc')

# Show dataset details

print(ds)

# Display variables specifically

print("\nData Variables:")

print(ds.data_vars)To check whether a specific variable (e.g., DIC) exists in an opened xarray dataset and retrieve detailed information about it, you can do the following:

import xarray as xr

# Load the dataset

ds = xr.open_dataset('/home/jovyan/erda_mount/theocean.nc')

# Check if 'DIC' exists in the dataset

if 'DIC' in ds.variables:

print("'DIC' variable found!\n")

# Print detailed info about the 'DIC' variable

print(ds['DIC'])

else:

print("'DIC' variable not found in the dataset.") 'DIC' variable found!Size: 3MB [696000 values with dtype=float32] Coordinates: * time (time) object 8B 1950-07-16 21:59:59.999997 * z_t (z_t) float32 240B 500.0 1.5e+03 2.5e+03 ... 5.125e+05 5.375e+05 ULONG (nlat, nlon) float64 93kB ... ULAT (nlat, nlon) float64 93kB ... TLONG (nlat, nlon) float64 93kB ... TLAT (nlat, nlon) float64 93kB ... Dimensions without coordinates: nlat, nlon Attributes: long_name: Dissolved Inorganic Carbon units: mmol/m^3 grid_loc: 3111 cell_methods: time: mean

For printing all variables and their long_name

import xarray as xr

# Open the NetCDF file

ds = xr.open_dataset('/home/jovyan/erda_mount/theocean.nc')

# Print all variables and their long_name

print("=== Variables and Their Descriptions ===\n")

for var in ds.variables:

long_name = ds[var].attrs.get('long_name', 'No long_name')

print(f"{var:20}: {long_name}")

=== Variables and Their Descriptions ===

time_bound : boundaries for time-averaging interval

moc_components : MOC component names

transport_components: T,S transport components

transport_regions : regions for all transport diagnostics

time : time

z_t : depth from surface to midpoint of layer

z_t_150m : depth from surface to midpoint of layer

z_w : depth from surface to top of layer

z_w_top : depth from surface to top of layer

z_w_bot : depth from surface to bottom of layer

lat_aux_grid : latitude grid for transport diagnostics

moc_z : depth from surface to top of layer

dz : thickness of layer k

dzw : midpoint of k to midpoint of k+1

ULONG : array of u-grid longitudes

ULAT : array of u-grid latitudes

TLONG : array of t-grid longitudes

TLAT : array of t-grid latitudes

To print detailed metadata of each variable in a NetCDF file, such as its data type, dimensions, and attributes (like long_name, units, _FillValue, missing_value, _ChunkSizes), you can use the following code

import xarray as xr

# Open dataset

ds = xr.open_dataset('/home/jovyan/erda_mount/theocean.nc')

# Loop through all variables

for var in ds.variables:

da = ds[var]

print(f"{da.dtype} {var}({', '.join(f'{dim}={ds.dims[dim]}' for dim in da.dims)});")

for attr, val in da.attrs.items():

print(f" :{attr} = {val!r};")

print() # Blank line between variables

object time_bound(time=1, d2=2);

:long_name = 'boundaries for time-averaging interval';

:cell_methods = 'time: mean';

|S256 moc_components(moc_comp=3);

:long_name = 'MOC component names';

:units = '';

|S256 transport_components(transport_comp=5);

:long_name = 'T,S transport components';

:units = '';

|S256 transport_regions(transport_reg=2);

:long_name = 'regions for all transport diagnostics';

:units = '';

object time(time=1);

:long_name = 'time';

:bounds = 'time_bound';

:cell_methods = 'time: mean';

float32 z_t(z_t=60);

:long_name = 'depth from surface to midpoint of layer';

:units = 'centimeters';

:positive = 'down';

:valid_min = np.float32(500.0);

:valid_max = np.float32(537500.0);

float32 z_t_150m(z_t_150m=15);

:long_name = 'depth from surface to midpoint of layer';

:units = 'centimeters';

:positive = 'down';

:valid_min = np.float32(500.0);

:valid_max = np.float32(14500.0);

float32 z_w(z_w=60);

:long_name = 'depth from surface to top of layer';

:units = 'centimeters';

:positive = 'down';

:valid_min = np.float32(0.0);

:valid_max = np.float32(525000.94);

float32 z_w_top(z_w_top=60);

:long_name = 'depth from surface to top of layer';

:units = 'centimeters';

:positive = 'down';

:valid_min = np.float32(0.0);

:valid_max = np.float32(525000.94);

float32 z_w_bot(z_w_bot=60);

:long_name = 'depth from surface to bottom of layer';

:units = 'centimeters';

:positive = 'down';

:valid_min = np.float32(1000.0);

:valid_max = np.float32(549999.06);

float32 lat_aux_grid(lat_aux_grid=105);

:long_name = 'latitude grid for transport diagnostics';

:units = 'degrees_north';

:valid_min = np.float32(-80.26017);

:valid_max = np.float32(90.0);

float32 moc_z(moc_z=61);

:long_name = 'depth from surface to top of layer';

:units = 'centimeters';

:positive = 'down';

:valid_min = np.float32(0.0);

:valid_max = np.float32(549999.06);

float32 dz(z_t=60);

:long_name = 'thickness of layer k';

:units = 'centimeters';

float32 dzw(z_w=60);

:long_name = 'midpoint of k to midpoint of k+1';

:units = 'centimeters';

float64 ULONG(nlat=116, nlon=100);

:long_name = 'array of u-grid longitudes';

:units = 'degrees_east';

float64 ULAT(nlat=116, nlon=100);

:long_name = 'array of u-grid latitudes';

:units = 'degrees_north';

float64 TLONG(nlat=116, nlon=100);

:long_name = 'array of t-grid longitudes';

:units = 'degrees_east';

float64 TLAT(nlat=116, nlon=100);

:long_name = 'array of t-grid latitudes';

:units = 'degrees_north';

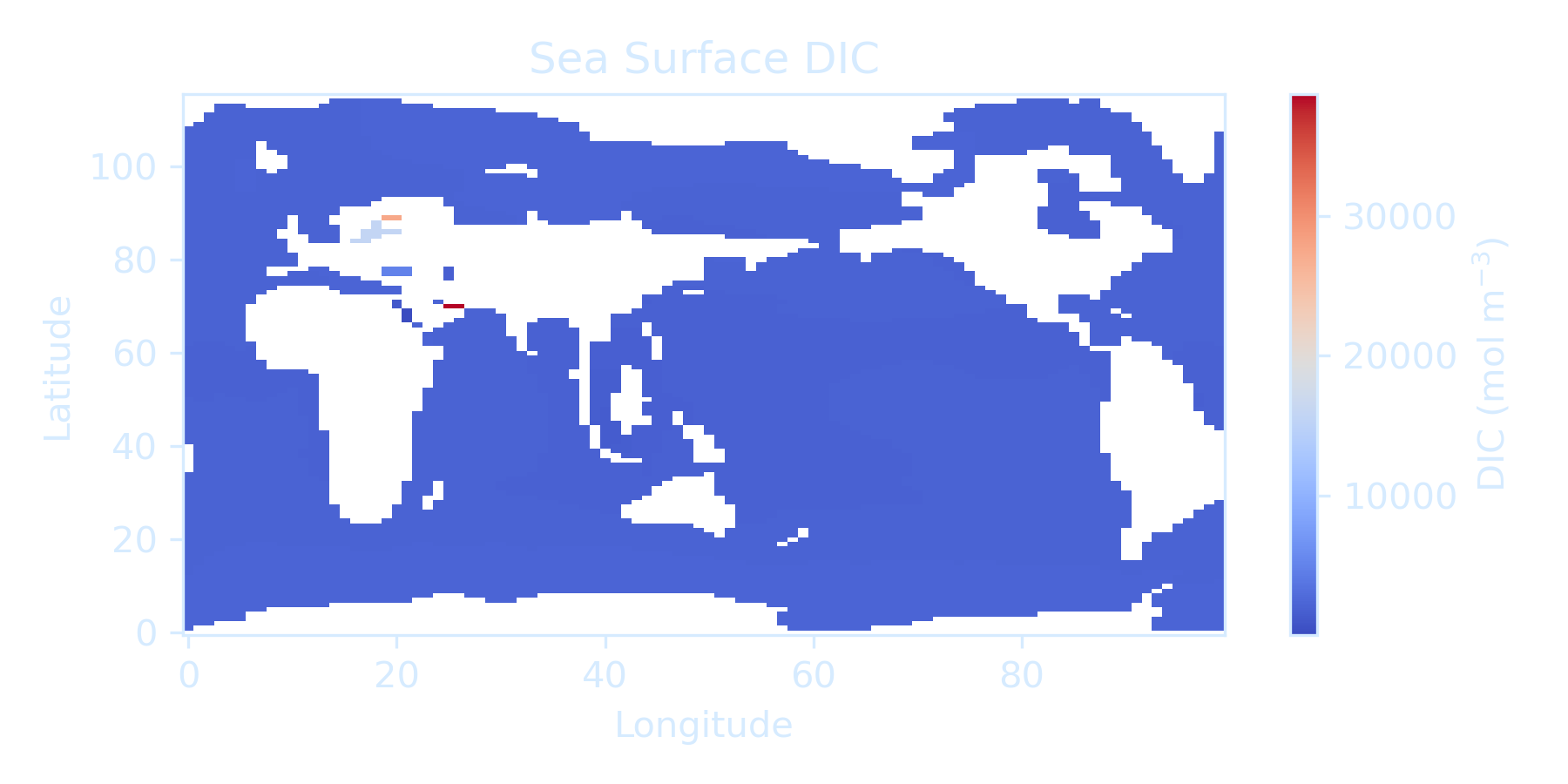

But if you plot it directly, the projection might seem incorrect due to the lack of proper geographic coordinates, suggest a need for proper coordinate projection handling (but this can be unnecessary depending on the goal and model). Based on the output, some effort regarding color bar handling is also needed for this assignment.

import xarray as xr

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load the dataset

ds = xr.open_dataset('/home/jovyan/erda_mount/theocean.nc')

# Select surface DIC (assuming variable DIC is 4D: time, z, y, x)

surface_DIC = ds['DIC'].isel(time=-1, z_t=0)

# Plotting the map of sea surface DIC

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 5), dpi = 300)

surface_DIC.plot.pcolormesh(

ax=ax,

cmap='coolwarm', # choose colormap here

shading='auto',

cbar_kwargs={'label': 'DIC (mol m$^{-3}$)'}

)

ax.set_title('Sea Surface DIC')

ax.set_xlabel('Longitude')

ax.set_ylabel('Latitude')

plt.tight_layout()

# Save the figure at the save folder

plt.savefig('./sea_surface_DIC.png', transparent=True)

plt.show()

Here's a quick cell you can run to inspect the coordinate system (dimensions, variable names, and their attributes) of your NetCDF file (theocean.nc)

import numpy as np

ds = xr.open_dataset('/home/jovyan/erda_mount/theocean.nc')

# Print coordinates specifically

print("\n--- Coordinate Variables ---")

for coord in ds.coords:

print(f"{coord}: {ds.coords[coord].dims} {ds.coords[coord].shape}")

# Print variable names and their dimensions

print("\n--- Data Variables ---")

for var in ds.data_vars:

print(f"{var}: {ds[var].dims} {ds[var].shape}")

# Print attributes of TLAT and TLONG if they exist

if 'TLAT' in ds:

print("\nTLAT attributes:", ds['TLAT'].attrs)

if 'TLONG' in ds:

print("\nTLONG attributes:", ds['TLONG'].attrs)

# Print random sample lat/lon points to verify

print("\n--- Sample Latitude and Longitude Points ---")

TLAT = ds['TLAT'].values

TLONG = ds['TLONG'].values

nlat, nlon = TLAT.shape

for _ in range(5):

i = np.random.randint(0, nlat)

j = np.random.randint(0, nlon)

print(f"Index (i={i}, j={j}) -> Lat: {TLAT[i, j]:.2f}°, Lon: {TLONG[i, j]:.2f}°")

--- Sample Latitude and Longitude Points ---

Index (i=98, j=26) -> Lat: 74.99°, Lon: 16.65°

Index (i=69, j=12) -> Lat: 21.58°, Lon: 6.38°

Index (i=54, j=6) -> Lat: 3.38°, Lon: 344.90°

Index (i=47, j=35) -> Lat: -0.90°, Lon: 89.30°

Index (i=50, j=94) -> Lat: 0.90°, Lon: 301.70°

Convert the domain from [0, 360] to [-180, 180], which is easier to interpret for many ocean regions.

# Surface map (latitude-longitude at surface level z_t=0)

dic_surface = ds['DIC'].isel(time=time_index, z_t=0)

lat_2d = ds['TLAT'].values

lon_2d = ds['TLONG'].values

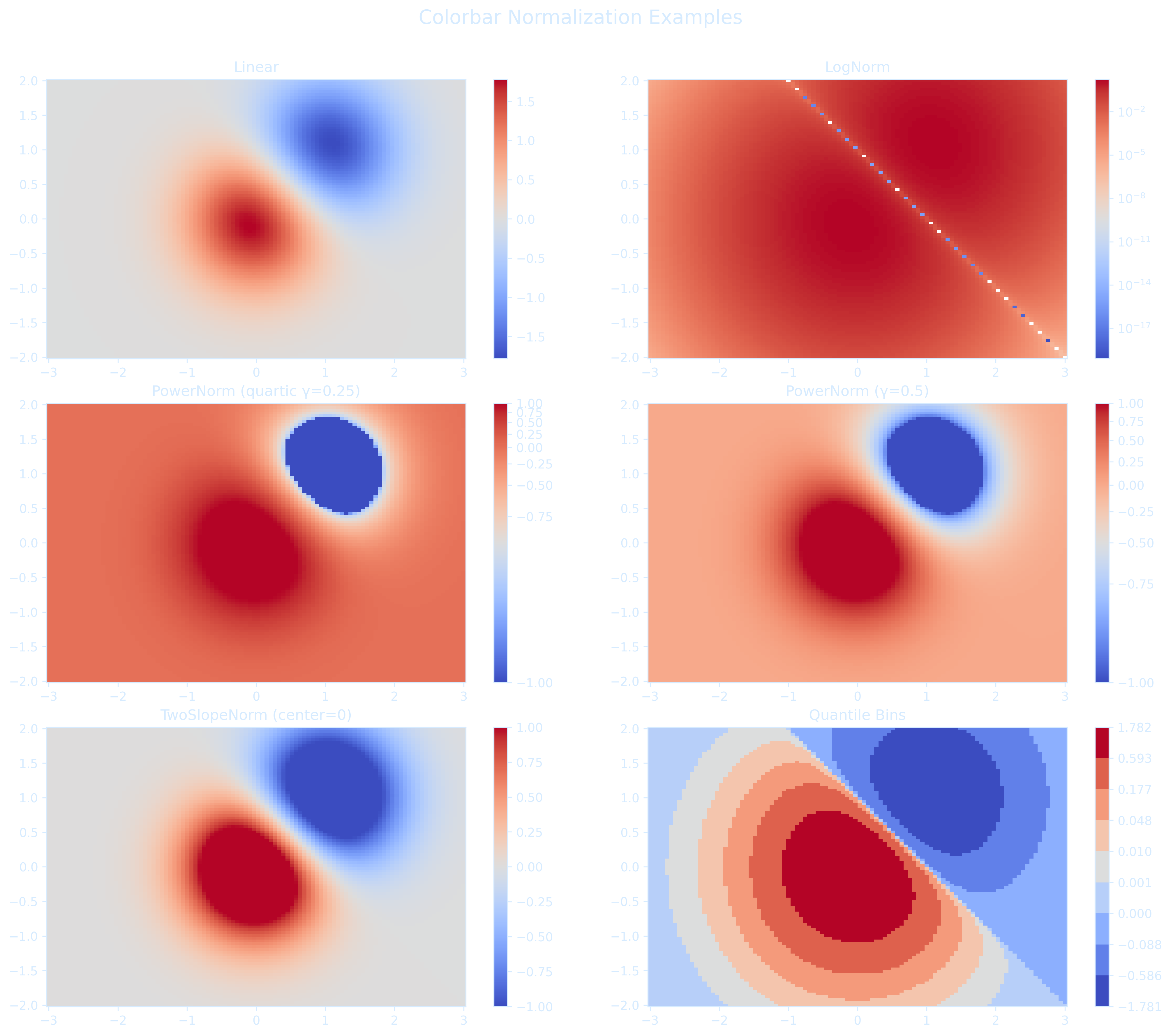

lon_2d = np.where(lon_2d > 180, lon_2d - 360, lon_2d) # Convert to [-180, 180]Choosing the appropriate colorbar normalization is important for accurately visualizing the range and structure of values in climate model output.

Matplotlib provides a rich set of beautiful colormaps for oceanography with excellent examples.

Here are some useful data-visualization examples using the seaborn library in Python: Customizing the Interface for Seaborn Heatmaps

Food for thought: Why Should Engineers and Scientists Be Worried About Color?

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import colors

# Create sample data

N = 100

X, Y = np.mgrid[-3:3:complex(0, N), -2:2:complex(0, N)]

Z1 = np.exp(-X**2 - Y**2)

Z2 = np.exp(-(X - 1)**2 - (Y - 1)**2)

Z = (Z1 - Z2) * 2

# Normalize options

vmin, vmax = -1.0, 1.0

norms = {

'Linear': None,

'LogNorm': colors.LogNorm(vmin=Z[Z > 0].min(), vmax=Z.max()),

'PowerNorm (quartic γ=0.25)': colors.PowerNorm(gamma=0.25, vmin=vmin, vmax=vmax),

'PowerNorm (γ=0.5)': colors.PowerNorm(gamma=0.5, vmin=vmin, vmax=vmax),

'TwoSlopeNorm (center=0)': colors.TwoSlopeNorm(vmin=vmin, vcenter=0, vmax=vmax),

'Quantile Bins': colors.BoundaryNorm(boundaries=np.quantile(Z, np.linspace(0, 1, 10)), ncolors=256)

}

# Plotting

plt.rcParams['text.color'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['axes.labelcolor'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['xtick.color'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['ytick.color'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['axes.edgecolor'] = '#d6ebff'

fig, axs = plt.subplots(nrows=3, ncols=2, figsize=(14, 12), dpi = 300)

axs = axs.ravel()

fig.patch.set_alpha(0)

for ax in axs:

ax.set_facecolor('none')

for ax, (name, norm) in zip(axs, norms.items()):

# LogNorm only works on positive values

if name == 'LogNorm':

pcm = ax.pcolormesh(X, Y, np.abs(Z), norm=norm, cmap='coolwarm', shading='auto')

else:

pcm = ax.pcolormesh(X, Y, Z, norm=norm, cmap='coolwarm', shading='auto')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax)

ax.set_title(name)

ax.set_aspect('equal')

plt.suptitle("Colorbar Normalization Examples", fontsize=16)

plt.tight_layout(rect=[0, 0, 1, 0.97])

plt.show()

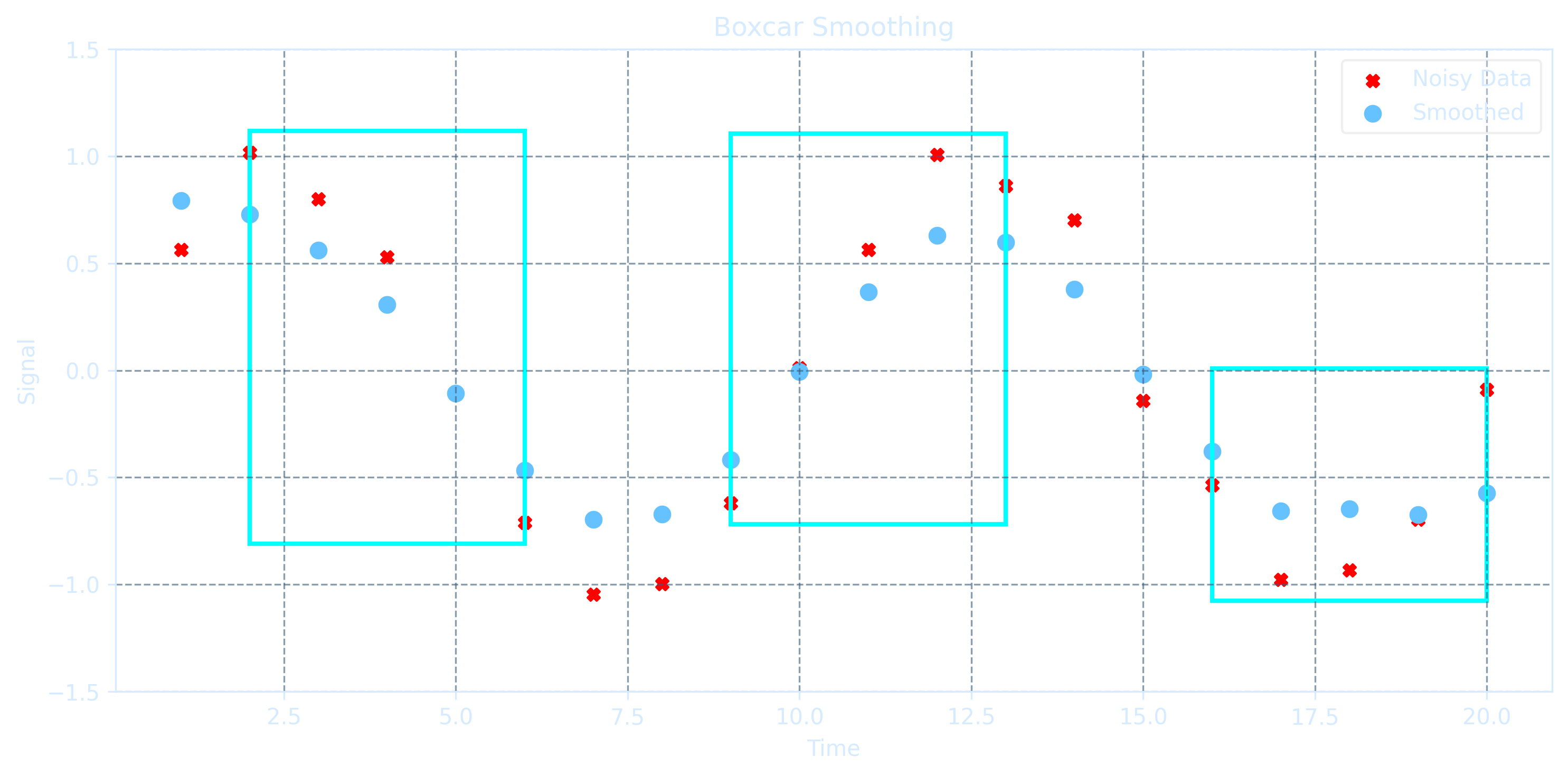

Boxcar Smoothing

Boxcar smoothing is a simple and effective smoothing technique that acts like a low-pass filter by removing high-frequency noise from data. It sums several neighboring points within a "box" window, averages them, and plots the averaged value at the center position.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.patches import Rectangle

# --- Generate clean sine signal ---

N = 20

dt = 1.0

A = 1.0

f = 0.1

omega = 2 * np.pi * f

timesteps = np.linspace(1, N, N)

signal = A * np.sin(omega * timesteps)

# --- Add noise ---

np.random.seed(1)

noise = 0.3 * (np.random.rand(N) - 0.5)

noisy_signal = signal + noise

# --- Boxcar smoothing ---

def boxcar_smooth(x, w):

smoothed = np.zeros_like(x)

half_w = w // 2

for i in range(len(x)):

left = max(0, i - half_w)

right = min(len(x), i + half_w + 1)

smoothed[i] = np.mean(x[left:right])

return smoothed

w = 5

smoothed_signal = boxcar_smooth(noisy_signal, w=w)

# --- Plot with styled settings ---

axis_color = '#d6ebff'

noise_color = 'red'

smooth_color = '#66c2ff'

box_color = '#00ffff'

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 5), dpi=300)

fig.patch.set_alpha(0.0)

ax.set_facecolor('none')

# Scatter noisy and smoothed data

ax.scatter(timesteps, noisy_signal, color=noise_color, s=30, label='Noisy Data', marker='X')

ax.scatter(timesteps, smoothed_signal, color=smooth_color, s=50, label='Smoothed')

# Draw example boxcar windows

for center in [3, 10, 17]:

left = max(0, center - w // 2)

right = min(N, center + w // 2 + 1)

x_min = timesteps[left]

x_max = timesteps[right - 1]

y_min = min(noisy_signal[left:right]) - 0.1

y_max = max(noisy_signal[left:right]) + 0.1

rect = Rectangle((x_min, y_min), x_max - x_min, y_max - y_min,

edgecolor=box_color, facecolor='none', lw=2)

ax.add_patch(rect)

ax.set_title("Boxcar Smoothing", color=axis_color)

ax.set_xlabel("Time", color=axis_color)

ax.set_ylabel("Signal", color=axis_color)

ax.set_ylim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax.grid(True, linestyle='--', color='#3c5c78', alpha=0.6)

# Legend

legend = ax.legend()

legend.get_frame().set_alpha(0.3)

for text in legend.get_texts():

text.set_color(axis_color)

# Axis ticks and spines

ax.tick_params(colors=axis_color)

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_color(axis_color)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The improvement in signal-to-noise ratio is proportional to the square root of the number of points inside the boxcar, but it comes with a trade-off: \( N-1 \) edge points are lost, and the data density decreases by a fraction of \(\frac{N-1}{N}\). If the boxcar size is too large relative to the data sampling rate, significant features can be smoothed out and lost. Therefore boxcar smoothing is best applied when the data are sampled at a sufficiently high rate compared to the underlying signal variation.

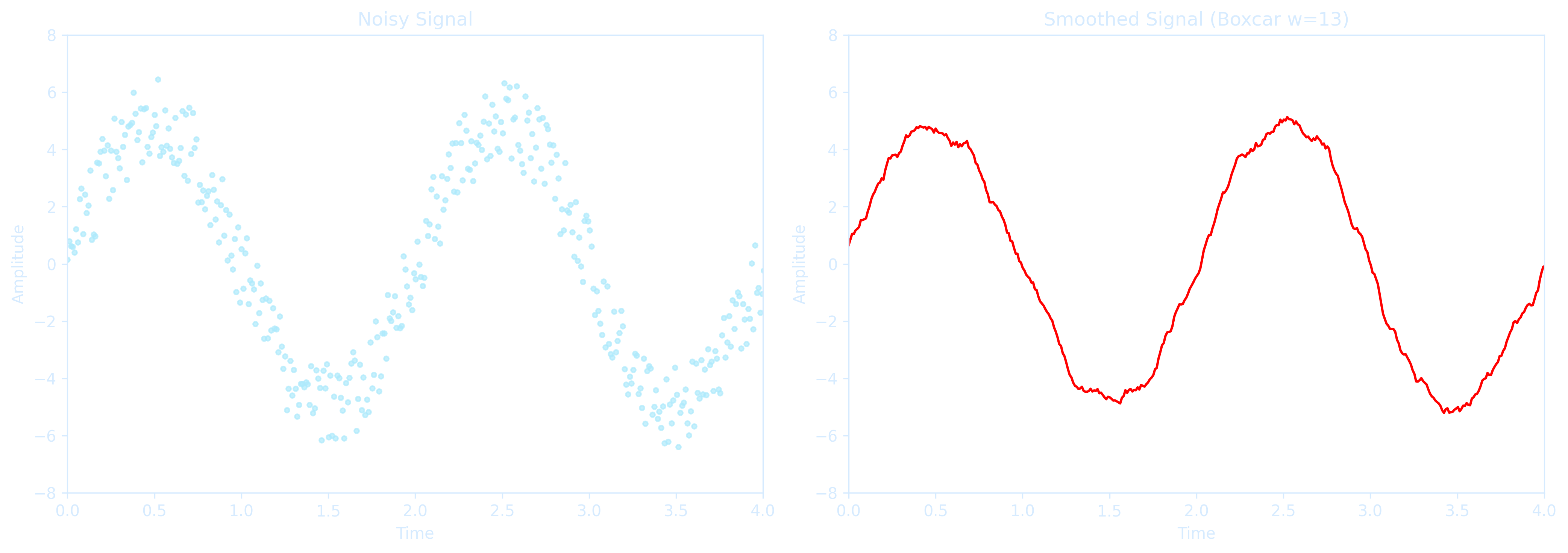

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# --- Generate clean sine signal ---

N = 1000 # Number of samples

dt = 1.0 / 100.0 # 100 samples/sec

A = 5.0 # Amplitude

f = 0.5 # Frequency in Hz

omega = 2 * np.pi * f

timesteps = np.linspace(0.0, N*dt, N)

signal = A * np.sin(omega * timesteps)

# --- Add noise ---

np.random.seed(0) # For reproducibility

noise = 3 * (np.random.rand(N) - 0.5) # Random noise centered around 0

noisy_signal = signal + noise

# --- Boxcar smoothing ---

def boxcar_smooth(x, w):

"""Smooth 1D array x using a boxcar (moving average) of width w."""

smoothed = np.zeros_like(x)

half_w = w // 2

for i in range(len(x)):

left = max(0, i - half_w)

right = min(len(x), i + half_w + 1)

smoothed[i] = np.mean(x[left:right])

return smoothed

smoothed_signal = boxcar_smooth(noisy_signal, w=13)

# --- Plot noisy vs smoothed with transparent background and styled text ---

axis_color = '#d6ebff' # light blue for axis

noise_color = '#aeeafc' # lighter color for noisy points

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 5), dpi=300)

fig.patch.set_alpha(0.0)

# Plot 1: Noisy Signal

axs[0].set_facecolor('none')

axs[0].plot(timesteps, noisy_signal, '.', color=noise_color, alpha=0.7) # Change color here

axs[0].set_xlim(0, 4)

axs[0].set_ylim(-8, 8)

axs[0].set_title("Noisy Signal", color=axis_color)

axs[0].tick_params(colors=axis_color)

axs[0].set_xlabel("Time", color=axis_color)

axs[0].set_ylabel("Amplitude", color=axis_color)

for spine in axs[0].spines.values():

spine.set_color(axis_color)

# Plot 2: Smoothed Signal

axs[1].set_facecolor('none')

axs[1].plot(timesteps, smoothed_signal, 'r')

axs[1].set_xlim(0, 4)

axs[1].set_ylim(-8, 8)

axs[1].set_title("Smoothed Signal (Boxcar w=13)", color=axis_color)

axs[1].tick_params(colors=axis_color)

axs[1].set_xlabel("Time", color=axis_color)

axs[1].set_ylabel("Amplitude", color=axis_color)

for spine in axs[1].spines.values():

spine.set_color(axis_color)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

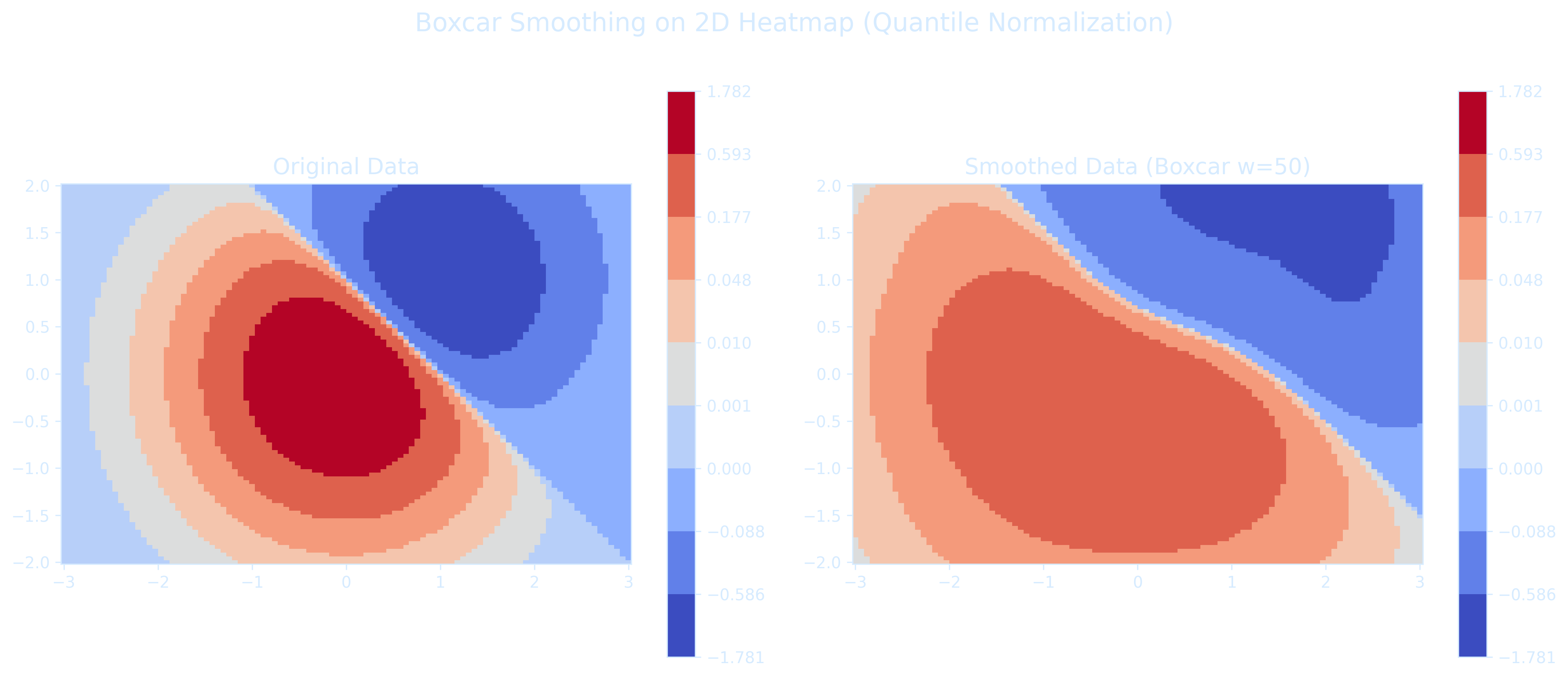

The code below shows how to apply the boxcar smoothing to 2D heatmap data before plotting, exactly like what we did for 1D signals

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import colors

# --- Generate Sample 2D Data ---

N = 100

X, Y = np.mgrid[-3:3:complex(0, N), -2:2:complex(0, N)]

Z1 = np.exp(-X**2 - Y**2)

Z2 = np.exp(-(X - 1)**2 - (Y - 1)**2)

Z = (Z1 - Z2) * 2

# --- Boxcar Smoothing 2D ---

def boxcar_smooth_2d(data, w):

smoothed = np.zeros_like(data)

half_w = w // 2

for i in range(data.shape[0]):

for j in range(data.shape[1]):

left_i = max(0, i - half_w)

right_i = min(data.shape[0], i + half_w + 1)

left_j = max(0, j - half_w)

right_j = min(data.shape[1], j + half_w + 1)

smoothed[i, j] = np.mean(data[left_i:right_i, left_j:right_j])

return smoothed

Z_smoothed = boxcar_smooth_2d(Z, w=50)

# --- Quantile Bin Normalization ---

boundaries = np.quantile(Z, np.linspace(0, 1, 10))

quantile_norm = colors.BoundaryNorm(boundaries=boundaries, ncolors=256)

# --- Plotting Style Settings ---

plt.rcParams['text.color'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['axes.labelcolor'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['xtick.color'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['ytick.color'] = '#d6ebff'

plt.rcParams['axes.edgecolor'] = '#d6ebff'

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 6), dpi=300)

fig.patch.set_alpha(0)

for ax in axs:

ax.set_facecolor('none')

# --- Plot Original ---

pcm1 = axs[0].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z, norm=quantile_norm, cmap='coolwarm', shading='auto')

fig.colorbar(pcm1, ax=axs[0])

axs[0].set_title('Original Data', fontsize=14)

axs[0].set_aspect('equal')

# --- Plot Smoothed ---

pcm2 = axs[1].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z_smoothed, norm=quantile_norm, cmap='coolwarm', shading='auto')

fig.colorbar(pcm2, ax=axs[1])

axs[1].set_title('Smoothed Data (Boxcar w=50)', fontsize=14)

axs[1].set_aspect('equal')

plt.suptitle('Boxcar Smoothing on 2D Heatmap (Quantile Normalization)', fontsize=16)

plt.tight_layout(rect=[0, 0, 1, 0.96])

plt.show()